Touching Time: The Plaster Cast Hands of GF Watts

Research Associate Helen Victoria Murray updates on her archives and collections research, the experience of examining the plaster cast hands of GF Watts.

I’m visiting the sculpture gallery at Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village. Before me, an assortment of tagged and catalogued Victorian plaster casts, each one a hand of different shape, size, pose or provenance. I can see children’s hands, women’s hands, and even celebrity hands. Why so many? What was their purpose?

Plaster cast hands on display in the sculpture gallery at Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village. Photography by Helen Victoria Murray

When Michael Brown and Joanne Begiato first conceived The Victorian Hand, they took inspiration from the hands of the Symbolist painter, George Frederic Watts, and his wife, the artist and ceramicist Mary Seaton Watts. Their plaster cast is displayed in Watts’s reconstructed studio home, Limnerslease in Compton Surrey, clasped in permanent union. George and Mary’s plaster hands are richly evocative, not only of the couple’s shared emotional history, but the significance of hands in creative practice. The identity and relationship of the artists, embodied in this artefact gestures to cultural reasons for Watts Gallery’s large collection of plaster hands.

COMWG2007.933.1, Cast of the Left Hands of G. F. Watts and Mary Seaton Watts Watts, 20 Nov 1886. Photograph Courtesy of Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village.

Throughout the nineteenth century, plaster cast hands were a popular memento to commemorate sentimental relationships: a gift between spouses, or parent and child. These sentimental relationships even extended to celebrities – from surgeons to poets to psychic mediums, casts of famous hands were cultural curios.

COMWG2007.1043.1 - Plaster Cast of the Left Hand of Abraham Lincoln. Photograph by Helen Victoria Murray.

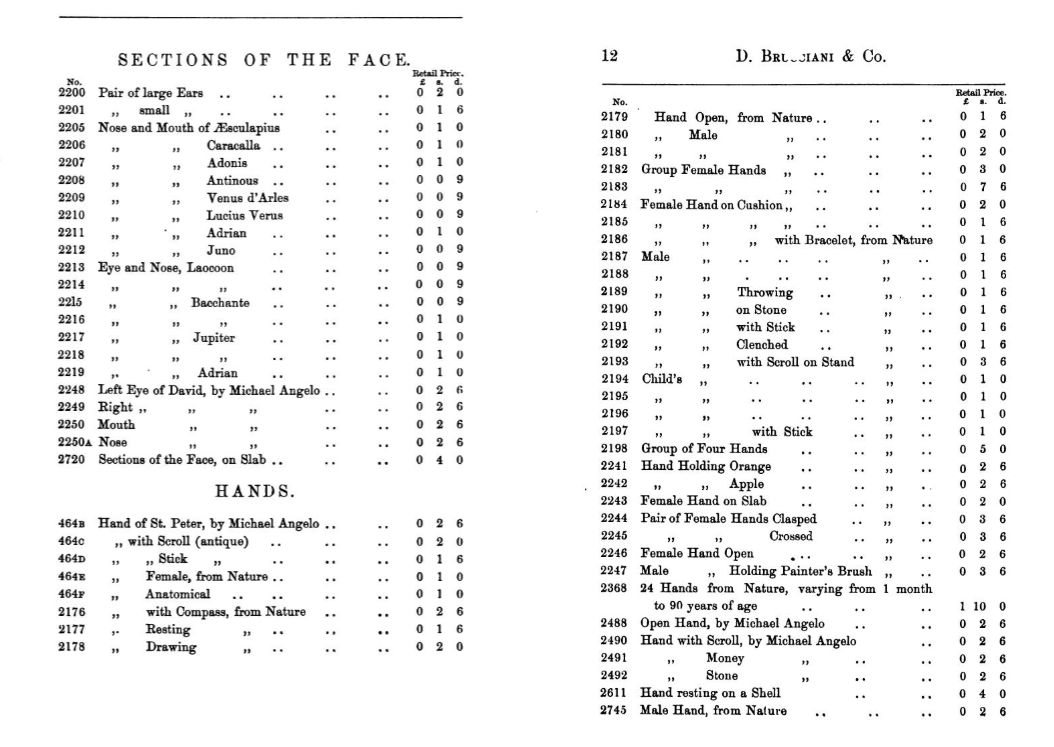

Cast hands were highly valued in the Victorian market of sentiment. For artists like Watts, they were a practical tool. Plaster cast makers and suppliers, known as formatore, such as Domenico Brucciani, maintained a busy trade in plaster casts, both for individuals and art schools. Some of these casts were copies from classical antiquity, while others were cast from the life. Students of Fine Art learned form and anatomy from casts before graduating to life models.

In 1875, Watts wrote to Jane Nassau Senior about her nephew, whom Watts was tutoring:

I told him to get his little sister to place her hand on the table and hold it steady when he drew it. […] I am satisfied he has the natural gifts. […] I remember you had some casts, simplified forms of heads and hands; if you have them will you send them?

- G.F. Watts to Jane Nassau Senior, Nov 21, 1875 (GFW/1/10/9, p11, GF Watts Archive, National Portrait Gallery, London).

This letter shows the child’s facility to draw a hand as a recognisable indicator of budding talent, and an exercise to develop skill.

Casts weren’t only used by beginners, but throughout an artist’s career. The human hand poses a challenge of technical anatomy, and creative expression. Its forms are intricate and changeful; their emotive gestures still more nuanced. Owning plaster casts of the hand could help artists with their preparatory studies: a gesture, fleeting in life, could be studied at length.

Several of the casts in the Watts collection relate to one particular painting – G.F. Watts’s Time, Death and Judgement. In this painting, the gestural force of Time’s hand, striding forward, wielding his scythe, is crucial for the vitality of the allegory.

My collections research shows that Watts put significant effort into perfecting Time’s hand. In a study for the painting, held in the Ashmolean Museum, Time’s hand is an unrefined fist – hinting at the necessity of a reference from which Watts could study the finger pose. Further drawings from the Watts Gallery catalogue show Watts working through Time’s clenched hand from different angles as quick studies.

Watts had a practice of making sculptural maquettes as studies, even for artworks he intended to be two-dimensional paintings. As well as studying a cast of a hand holding a rod, Watts modelled Time’s hand pose at a monumental scale – signing his name in the hollow of the plaster, which tells us precisely that this piece was modelled for Time, Death and Judgement.

GF Watts is often seen as a cerebral, rather than embodied artist. He was described by fellow-artist Edward Burne-Jones as ‘the painter who thought, not the painter who painted’ (Rooke, p139). Yet, observing Watts’s hand-sculpted maquettes, we see an artist reasoning by hand, thinking in 3 dimensions to create tactile, embodied artworks.

Viewed under the natural light that streams in through Watts Gallery’s large picture window, shade and contrast create a fascinating sense of aliveness in the assortment of plaster hands. A successful cast records flesh and musculature; surfaces of fingernails; textural skin creases. We’re seeing a fleeting moment of embodiment, captured and held for over a century. At the same time, the casts’ surface texture is materially changed by interventions of time and conditions. As viewers, we are both intimately close and temporally distanced.

Time feels tangible in these casts.

Among the most poignant hands are Watts’s own, cast postmortem. Mary Watts’s written account of her husband’s final days abounds with intimate tactile contact. She writes on 30 June 1904, ‘I buried my face in his beloved hand.’ Yet Watts’s handwork did not end with his death. Mary narrates:

Cantoni [the plaster cast formatori] did the cast of the beloved features & the hands – & now under the exquisite pall – with flowers & light lilies in his empty studio. – The month since he stood there & laid by his work.

- Mary Seaton Watts, Diaries, Saturday July 2, 1904.

COMWG2007.933.2, Death Cast of G. F. Watts's Hands on a Circular Base, 1904. Photograph by Helen Victoria Murray.

As Hilary Underwood, archivist and curatorial consultant at Watts Gallery discussed with me, this cast shows visible signs of wastage and emaciation. Beneath Watts’s folded hands, the surface of a textile backdrop suggests a rapid casting process. Watts passed away in the height of Summer. The plaster cast, as with other funeral arrangements for the body’s lying-in, would have had to be completed quickly, to prevent accelerating decomposition in the warm weather. Time was of the essence.

This death cast materialises a summation of Watts’s career, as well as the end of life. For me as a researcher, the opportunity to handle and look closely at these plaster hands brings home the multiplicity of meanings cradled within representations of the hand. The many hands in Watts Gallery’s collection embody practice, and self-development as well as sentiment. G.F. Watts’s collection of plaster cast hands gesture to the life cycle of a Victorian artist, from learning and observation, to the honing of craft, the building of connections, and the preservation of life’s legacy.

Thanks to the Curatorial Team at Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village for their support and encouragement of our research.

References

Domenico Brucciani, Catalogue of Casts for Schools (Brucciani & Co, 1889)

Thomas Rooke, Burne-Jones Talking: His Conversations 1895-1898, ed by Mary Lago (Pallas Athene: 2023)

Rebecca Wade, Domenico Brucciani and the Formatori of 19th-century Britain (Bloomsbury, 2018)

G.F. Watts to Jane Nassau Senior, Nov 21, 1875 (GFW/1/10/9, p11, GF Watts Archive, National Portrait Gallery, London)

Mary Seaton Watts, Diaries, Saturday July 2, 1904.